what fort was attacked to begin the civil war

| Boxing of Fort Sumter | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Ceremonious War | |||||||

Battery of Fort Sumter by Currier & Ives | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| | | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Robert Anderson | P. Yard. T. Beauregard | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Eastward Battery, 1st United states of america Artillery Regiment | Provisional Forces of the Amalgamated States | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 85[two] [3] | 500–6,000 (estimated)[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 0[5] | 0[5] | ||||||

The Boxing of Fort Sumter (April 12–xiii, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter nigh Charleston, Due south Carolina past the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender by the United States Ground forces, beginning the American Civil War.

Following the announcement of secession past South Carolina on December 20, 1860, its authorities demanded that the U.S. Army abandon its facilities in Charleston Harbor. On Dec 26, Major Robert Anderson of the U.S. Army surreptitiously moved his small command from the vulnerable Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island to Fort Sumter, a substantial fortress built on an island controlling the entrance of Charleston Harbor. An endeavour by U.S. President James Buchanan to reinforce and resupply Anderson using the unarmed merchant ship Star of the Westward failed when it was fired upon past shore batteries on January 9, 1861. Southward Carolina government and so seized all Federal property in the Charleston area except for Fort Sumter.

During the early on months of 1861, the situation effectually Fort Sumter increasingly began to resemble a siege. In March, Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard, the first full general officer of the newly formed Amalgamated States Ground forces, was placed in command of Confederate forces in Charleston. Beauregard energetically directed the strengthening of batteries around Charleston harbor aimed at Fort Sumter. Conditions in the fort deteriorated due to shortages of men, nutrient, and supplies as the Marriage soldiers rushed to complete the installation of boosted guns.

The resupply of Fort Sumter became the first crisis of the administration of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, inaugurated March iv, 1861, post-obit his victory in the ballot of November 6, 1860. He notified the Governor of South Carolina, Francis W. Pickens, that he was sending supply ships, which resulted in an ultimatum from the Confederate authorities for the immediate evacuation of Fort Sumter, which Major Anderson refused. Kickoff at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, the Confederates bombarded the fort from artillery batteries surrounding the harbor. Although the Union garrison returned fire, they were significantly outgunned and, afterwards 34 hours, Major Anderson agreed to evacuate. In that location were no deaths on either side every bit a direct result of this engagement, although a gun explosion during the give up ceremonies on April xiv caused the death of two U.S. Army soldiers. The event oft regarded as the "Kickoff Mortality of the Ceremonious State of war" was the Baltimore riot of 1861, one week later.

Following the boxing, there was widespread back up from both North and S for further military action. Lincoln'southward immediate call for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion resulted in an additional iv Southern states also declaring their secession and joining the Confederacy. The boxing is ordinarily recognized as the first battle of the American Civil War.

Background

Secession

On Dec 20, 1860, shortly after Abraham Lincoln'southward victory in the presidential ballot of 1860, Due south Carolina adopted an ordinance declaring its secession from the U.s.a. of America, and by February 1861 half dozen more than Southern states had adopted similar ordinances of secession. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Amalgamated States of America and established their temporary uppercase at Montgomery, Alabama. A Feb peace conference met in Washington, D.C., but failed to resolve the crisis. The remaining 8 slave states declined pleas to join the Confederacy.[half-dozen] [7]

The seceding states seized Federal backdrop inside their boundaries, including buildings, arsenals, and fortifications. President James Buchanan protested but took no activity. Buchanan was concerned that an overt action could crusade the remaining slave states to exit the Union, and while he idea that at that place was no constitutional authority for a state to secede, he could find no constitutional dominance for him to deed to forestall it.[8] [9]

Forts of Charleston

Several forts had been constructed in Charleston's harbor, including Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, which were non among the sites seized initially. Fort Moultrie on Sullivan Island was the oldest—it was the site of fortifications since 1776—and was the headquarters of the U.S. Ground forces garrison. However, it had been designed as a gun platform for defending the harbor, and its defenses confronting country-based attacks were feeble; during the crisis, the Charleston newspapers commented that sand dunes had piled up against the walls in such a way that the wall could easily be scaled. When the garrison began immigration away the dunes, the papers objected.[10] [xi] [12]

Major Robert Anderson of the 1st U.S. Artillery regiment had been appointed to command the Charleston garrison that fall because of rising tensions. A native of Kentucky, he was a protégé of Winfield Scott, the general in chief of the Army, and was thought more capable of handling a crisis than the garrison'southward previous commander, Col. John L. Gardner, who was nearing retirement. Anderson had served an earlier bout of duty at Fort Moultrie and his father had been a defender of the fort (and then chosen Fort Sullivan) during the American Revolutionary War. Throughout the fall, Southward Carolina government considered both secession and the expropriation of federal property in the harbor to be inevitable. As tensions mounted, the surroundings around the fort increasingly resembled a siege, to the point that the South Carolina authorities placed picket ships to discover the movements of the troops and threatened to attack when xl rifles were transferred to ane of the harbor forts from the U.S. armory in the city.[2] [13] [14] [12]

In contrast to Moultrie, Fort Sumter dominated the entrance to Charleston Harbor and, though unfinished, was designed to exist one of the strongest fortresses in the world. In the fall of 1860 work on the fort was almost completed, but the fortress was thus far garrisoned by a single soldier, who functioned equally a lighthouse keeper, and a modest political party of noncombatant construction workers. Under the encompass of darkness on Dec 26, six days subsequently Southward Carolina declared its secession, Anderson abased the indefensible Fort Moultrie, ordering its guns spiked and its gun carriages burned, and surreptitiously relocated his command past small boats to Sumter.[15] [xvi]

President Buchanan and the Star of the West

South Carolina authorities considered Anderson's motility to be a breach of faith. Governor Francis W. Pickens believed that President Buchanan had fabricated implicit promises to him to keep Sumter unoccupied and suffered political embarrassment as a event of his trust in those promises. Buchanan, a onetime U.S. Secretary of State and diplomat, had used carefully crafted cryptic language to Pickens, promising that he would non "immediately" occupy information technology.[17] From Major Anderson'southward standpoint, he was merely moving his existing garrison troops from one of the locations under his command to another. He had received instructions from the War Section on December 11, written past Major Full general Don Carlos Buell, Assistant Adjutant Full general of the Army, approved by Secretary of War John B. Floyd:[17] [xviii]

[Y]ou are to hold possession of the forts in this harbor, and if attacked y'all are to defend yourself to the last extremity. The smallness of your force volition not allow you, peradventure, to occupy more than one of the three forts, but an assault on or endeavor to take possession of whatever one of them will exist regarded as an act of hostility, and yous may then put your control into either of them which you may deem most proper to increment its power of resistance. Yous are also authorized to take like steps whenever y'all have tangible testify of a design to keep to a hostile act.[nineteen]

Governor Pickens, therefore, ordered that all remaining Federal positions except Fort Sumter were to exist seized. State troops speedily occupied Fort Moultrie (capturing 56 guns), Fort Johnson on James Island, and the battery on Morris Isle. On December 27, an assail strength of 150 men seized the Wedlock-occupied Castle Pinckney fortification, in the harbor close to downtown Charleston, capturing 24 guns and mortars without bloodshed. On December 30, the Federal arsenal in Charleston was captured, resulting in the acquisition of more 22,000 weapons by the militia. The Confederates promptly made repairs at Fort Moultrie and dozens of new batteries and defence force positions were constructed throughout the Charleston harbor surface area, including an unusual floating battery, and armed with weapons captured from the arsenal.[N i]

President Buchanan was surprised and dismayed at Anderson'due south move to Sumter, unaware of the dominance Anderson had received. However, he refused Pickens's need to evacuate Charleston harbor. Since the garrison'southward supplies were express, Buchanan authorized a relief expedition of supplies, pocket-size artillery, and 200 soldiers. The original intent was to ship the Navy sloop-of-state of war USS Brooklyn, but it was discovered that Confederates had sunk some derelict ships to block the shipping aqueduct into Charleston and in that location was concern that Brooklyn had too deep a typhoon to negotiate the obstacles. Instead, it seemed prudent to ship an unarmed civilian merchant ship, Star of the Due west, which might be perceived as less provocative to the Confederates. Equally Star of the W approached the harbor entrance on Jan ix, 1861, it was fired upon by a battery on Morris Island, which was staffed by cadets from The Citadel, amidst them William Stewart Simkins, who were the just trained artillerymen in the service of Due south Carolina at the time. Batteries from Fort Moultrie joined in and Star of the West was forced to withdraw. Major Anderson prepared his guns at Sumter when he heard the Amalgamated fire, but the secrecy of the operation had kept him unaware that a relief expedition was in progress and he chose not to start a full general engagement.[23] [24] [25] [2]

In a letter delivered January 31, 1861, Governor Pickens demanded of President Buchanan that he surrender Fort Sumter because, "I regard that possession is not consequent with the dignity or safety of the State of Southward Carolina."[26]

Preparations for state of war

Fort Sumter before the battle

Conditions at the fort were difficult during the winter of 1860–1861. Rations were brusque and fuel for heat was express. The garrison scrambled to consummate the defenses as best they could. Fort Sumter was designed to mount 135 guns, operated past 650 officers and men, but structure had met with numerous delays for decades and upkeep cuts had left it only most 90 percent finished in early 1861. Anderson's garrison consisted of just 85 men, primarily fabricated upward of two small arms companies: Company East, 1st U.South. Artillery, commanded by Capt. Abner Doubleday, and Company H, commanded past Capt. Truman Seymour. There were half-dozen other officers present: Surgeon Samuel W. Crawford, First Lt. Theodore Talbot of Company H, Offset Lt. Jefferson C. Davis of the 1st U.S. Artillery, and Second Lt. Norman J. Hall of Visitor H. Capt. John Grand. Foster and First Lt. George W. Snyder of the Corps of Engineers were responsible for the construction of the Charleston forts, but they reported to their headquarters in Washington, non straight to Anderson. The remaining personnel were 68 noncommissioned officers and privates, eight musicians, and 43 civilian workmen.[two]

By April the Union troops had positioned lx guns, but they had insufficient men to operate them all. The fort consisted of three levels of enclosed gun positions, or casemates. The second level of casemates was unoccupied. The majority of the guns were on the kickoff level of casemates, on the upper level (the parapet or barbette positions), and on the eye parade field. Unfortunately for the defenders, the original mission of the fort—harbor defence force—meant that it was designed and so that the guns were primarily aimed at the Atlantic, with little adequacy of protecting from artillery fire from the surrounding land or from infantry conducting an amphibious assault.[27] [28] [29]

In March, Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard took control of Southward Carolina forces in Charleston; on March one, President Jefferson Davis had appointed him the outset general officer in the armed forces of the new Confederacy,[thirty] specifically to take control of the siege. Beauregard made repeated demands that the Union force either give up or withdraw and took steps to ensure that no supplies from the metropolis were available to the defenders, whose food was running low. He likewise increased drills amongst the South Carolina militia, training them to operate the guns they manned. Major Anderson had been Beauregard'due south artillery teacher at West Point; the two had been particularly close, and Beauregard had become Anderson'south banana later on graduation. Both sides spent March drilling and improving their fortifications to the all-time of their abilities.[31]

Beauregard, a trained war machine engineer, congenital upward overwhelming strength to claiming Fort Sumter. Fort Moultrie had three 8-inch Columbiads, 2 8-inch howitzers, 5 32-pound smoothbores, and four 24-pounders. Outside of Moultrie were five ten-inch mortars, 2 32-pounders, two 24-pounders, and a 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbore. The floating battery next to Fort Moultrie had two 42-pounders and two 32-pounders on a raft protected by iron shielding. Fort Johnson on James Island had 1 24-pounder and four 10-inch mortars. At Cummings Indicate on Morris Island, the Confederates had emplaced seven 10-inch mortars, two 42-pounders, an English Blakely rifled cannon, and iii 8-inch Columbiads, the latter in the so-called Iron Battery, protected by a wooden shield faced with iron bars. Most half dozen,000 men were available to man the artillery and to attack the fort, if necessary, including the local militia, young boys and older men.[32]

Decisions for war

On March four, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated every bit president. He was almost immediately confronted with the surprise information that Major Anderson was reporting that only half-dozen weeks of rations remained at Fort Sumter. A crisis similar to the i at Fort Sumter had emerged at Pensacola, Florida, where Confederates threatened some other U.Due south. fortification—Fort Pickens. Lincoln and his new cabinet struggled with the decisions of whether to reinforce the forts, and how. They were also concerned about whether to have actions that might start open hostilities and which side would exist perceived equally the assaulter as a result. Like discussions and concerns were occurring in the Confederacy.[33] [34]

After the germination of the Amalgamated States of America in early February, there was some debate amidst the secessionists whether the capture of the fort was rightly a thing for South Carolina or for the newly declared national government in Montgomery, Alabama. South Carolina Governor Pickens was among united states' rights advocates who thought that all belongings in Charleston harbor had reverted to South Carolina upon that state'due south secession every bit an independent commonwealth. This debate ran alongside another give-and-take about how aggressively the installations—including Forts Sumter and Pickens—should exist obtained. President Davis, like his counterpart in Washington, preferred that his side not be seen every bit the aggressor. Both sides believed that the first side to use force would lose precious political support in the edge states, whose allegiance was undetermined; before Lincoln's inauguration on March 4, five states had voted against secession, including Virginia, and Lincoln openly offered to evacuate Fort Sumter if information technology would guarantee Virginia'southward loyalty. When asked about that offer, Abraham Lincoln commented, "A state for a fort is no bad business concern."[35]

The South sent delegations to Washington, D.C., and offered to pay for the Federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with the Amalgamated agents because he did not consider the Confederacy a legitimate nation and making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it equally a sovereign government. Nonetheless, Secretary of State William H. Seward, who wished to give up Sumter for political reasons—equally a gesture of good volition—engaged in unauthorized and indirect negotiations that failed.[36]

On April 4, as the supply state of affairs on Sumter became critical, President Lincoln ordered a relief expedition, to exist commanded by a former naval captain (and time to come Assistant Secretary of the Navy) Gustavus V. Fox, who had proposed a plan for nighttime landings of smaller vessels than the Star of the Westward. Trick's orders were to land at Sumter with supplies only, and if he was opposed past the Confederates, to reply with the U.S. Navy vessels following and to then land both supplies and men. This fourth dimension, Maj. Anderson was informed of the impending expedition, although the inflow date was not revealed to him. On April half-dozen, Lincoln notified Governor Pickens that "an attempt will be made to supply Fort Sumter with provisions simply, and that if such attempt be non resisted, no try to throw in men, arms, or ammunition will be made without further notice, [except] in case of an attack on the fort."[37] [38] [39] [40] [2]

Lincoln'southward notification had been fabricated to the governor of Southward Carolina, not the new Confederate government, which Lincoln did not recognize. Pickens consulted with Beauregard, the local Confederate commander. Soon President Davis ordered Beauregard to repeat the demand for Sumter'due south give up, and if information technology did not, to reduce the fort before the relief expedition arrived. The Confederate cabinet, coming together in Montgomery, endorsed Davis's gild on April 9. But Secretary of Land Robert Toombs opposed this decision: he reportedly told Jefferson Davis the attack "will lose us every friend at the Due north. You will only strike a hornet's nest. ... Legions now tranquility will swarm out and sting us to death. Information technology is unnecessary. Information technology puts us in the wrong. It is fatal."[41]

Beauregard dispatched aides—Col. James Chesnut, Col. James A. Chisholm, and Capt. Stephen D. Lee—to Fort Sumter on April 11 to issue the ultimatum. Anderson refused, although he reportedly commented, "I shall await the first shot, and if yous do non batter us to pieces, we shall be starved out in a few days." The aides returned to Charleston and reported this comment to Beauregard. At 1 a.m. on Apr 12, the aides brought Anderson a bulletin from Beauregard: "If you will state the time which you will evacuate Fort Sumter, and agree in the meantime that y'all volition not utilise your guns confronting u.s. unless ours shall be employed against Fort Sumter, we will abstain from opening fire upon you lot." Afterwards consulting with his senior officers, Maj. Anderson replied that he would evacuate Sumter by noon, April 15, unless he received new orders from his regime or additional supplies. Col. Chesnut considered this answer to exist too conditional and wrote a reply, which he handed to Anderson at 3:20 a.m.: "Sir: by authorisation of Brigadier Full general Beauregard, commanding the Conditional Forces of the Amalgamated States, we have the accolade to notify you that he will open fire of his batteries on Fort Sumter in one hr from this fourth dimension." Anderson escorted the officers back to their boat, shook hands with each one, and said "If we never encounter in this world over again, God grant that we may see in the next."[42] [43] [44] [45]

Bombardment

Bombardment of the Fort by the Confederates

At four:xxx a.m. on Apr 12, 1861, Lt. Henry S. Farley, acting upon the command of Capt. George S. James,[46] [47] fired a single 10-inch mortar circular from Fort Johnson. (James had offered the first shot to Roger Pryor, a noted Virginia secessionist, who declined, maxim, "I could not burn down the first gun of the war.") The shell exploded over Fort Sumter every bit a signal to open the general bombardment from 43 guns and mortars at Fort Moultrie, Fort Johnson, the floating battery, and Cummings Signal. Under orders from Beauregard, the guns fired in a counterclockwise sequence around the harbor, with ii minutes between each shot; Beauregard wanted to conserve ammunition, which he calculated would final for only 48 hours. Edmund Ruffin, another noted Virginia secessionist, had traveled to Charleston to be present at the beginning of the war, and fired ane of the kickoff shots at Sumter afterwards the signal circular, a 64-pound shell from the Iron Battery at Cummings Point. The shelling of Fort Sumter from the batteries ringing the harbor awakened Charleston'south residents (including diarist Mary Chesnut), who rushed out into the predawn darkness to watch the shells arc over the water and burst inside the fort.[48] [N 2]

Major Anderson held his fire, awaiting daylight. His troops reported for a call at vi a.m. so had breakfast. At 7 a.m., Capt. Abner Doubleday fired a shot at the Ironclad Battery at Cummings Point. He missed. Given the bachelor manpower, Anderson could not accept advantage of all of his 60 guns. He deliberately avoided using guns that were situated in the fort where casualties were most probable. The fort'south best cannons were mounted on the uppermost of its three tiers—the barbette tier—where his troops were most exposed to incoming fire from overhead. The fort had been designed to withstand a naval assault, and naval warships of the fourth dimension did not mount guns capable of elevating to shoot over the walls of the fort. However, the state-based cannons manned by the Confederates were capable of high-arcing ballistic trajectories and could therefore fire at parts of the fort that would have been out of naval guns' reach. Fort Sumter's garrison could but safely fire the 21 working guns on the lowest level, which themselves, because of the limited elevation immune past their embrasures, were largely incapable of delivering burn down with trajectories high enough to seriously threaten Fort Moultrie. Moreover, although the Federals had moved as many of their supplies to Fort Sumter every bit they could manage, the fort was quite depression on ammunition and was nearly out at the end of the 34-60 minutes bombardment. A more immediate trouble was the scarcity of textile gunpowder cartridges or bags; only 700 were available at the beginning of the boxing and workmen sewed frantically to create more, in some cases using socks from Anderson's personal wardrobe. Because of the shortages, Anderson reduced his firing to only half-dozen guns: two aimed at Cummings Point, two at Fort Moultrie, and two at the Sullivan'south Island batteries.[50] [51]

Ships from Trick's relief expedition began to arrive on Apr 12. Although Fox himself arrived at three a.m. on his steamer Baltic, nearly of the rest of his fleet was delayed until 6 p.m., and one of the two warships, USS Powhatan, never did get in. Unbeknownst to Fox, it had been ordered to the relief of Fort Pickens in Florida. As landing craft were sent toward the fort with supplies, the artillery fire deterred them and they pulled back. Fox decided to wait until after night and for the arrival of his warships. The next day, heavy seas made it difficult to load the small-scale boats with men and supplies and Fox was left with the hope that Anderson and his men could concord out until dark on April 13.[52]

Although Sumter was a masonry fort, there were wooden buildings within for barracks and officer quarters. The Confederates targeted these with heated shot (cannonballs heated red hot in a furnace), starting fires that could prove more dangerous to the men than explosive arms shells. At 7 p.one thousand. on April 12, a rain shower extinguished the flames and, at the aforementioned time, the Union gunners stopped firing for the night. They slept fitfully, concerned about a potential infantry assault against the fort. During the darkness, the Confederates reduced their burn to iv shots each hour. The following morning, the full battery resumed and the Confederates continued firing hot shot confronting the wooden buildings. By apex most of the wooden buildings in the fort and the principal gate were on burn. The flames moved toward the principal ammunition magazine, where 300 barrels of gunpowder were stored. The Union soldiers frantically tried to move the barrels to safety, just two-thirds were left when Anderson judged it was besides dangerous and ordered the mag doors closed. He ordered the remaining barrels thrown into the sea, but the tide kept floating them back together into groups, some of which were ignited past incoming artillery rounds. He also ordered his crews to redouble their efforts at firing, but the Confederates did the same, firing the hot shots almost exclusively. Many of the Confederate soldiers admired the courage and determination of the Yankees. When the fort had to suspension its firing, the Confederates often cheered and applauded afterwards the firing resumed and they shouted epithets at some of the nearby Union ships for failing to come to the fort'south aid.[53] [54]

Surrender

The fort's central flagpole was knocked down at ane p.thou. on April 13, raising doubts among the Confederates almost whether the fort was fix to surrender. Col. Louis Wigfall, a former U.S. senator, had been observing the battle and decided that this indicated the fort had had enough punishment. He commandeered a small boat and proceeded from Morris Isle, waving a white handkerchief from his sword, dodging incoming rounds from Sullivan's Island. Meeting with Major Anderson, he said, "You take defended your flag nobly, Sir. Y'all have done all that it is possible to practise, and General Beauregard wants to stop this fight. On what terms, Major Anderson, will you evacuate this fort?" Anderson was encouraged that Wigfall had said "evacuate," non "give up." He was low on armament, fires were burning out of control, and his men were hungry and exhausted. Satisfied that they had defended their post with accolade, enduring over three,000 Confederate rounds without losing a human, Anderson agreed to a truce at 2:00 p.k.[55] [56]

Fort Sumter raised Wigfall's white handkerchief on its flagpole as Wigfall departed in his small gunkhole back to Morris Isle, where he was hailed equally a hero. The handkerchief was spotted in Charleston and a delegation of officers representing Beauregard—Stephen D. Lee, Porcher Miles, a former mayor of Charleston, and Roger Pryor—sailed to Sumter, unaware of Wigfall'south visit. Anderson was outraged when these officers disavowed Wigfall's potency, telling him that the former senator had non spoken with Beauregard for two days, and he threatened to resume firing. Meanwhile, General Beauregard himself had finally seen the handkerchief and sent a 2d gear up of officers, offering essentially the aforementioned terms that Wigfall had presented, so the understanding was reinstated.[55] [57] [58]

The Matrimony garrison formally surrendered the fort to Amalgamated personnel at 2:xxx p.grand., April xiii. No one from either side was killed during the battery. During the 100-gun salute to the U.S. flag—Anderson's one status for withdrawal—a pile of cartridges blew up from a spark, mortally wounding privates Daniel Hough and Edward Galloway, and seriously wounding the other 4 members of the gun coiffure; these were the showtime military fatalities of the state of war. The salute was stopped at 50 shots. Hough was cached in the Fort Sumter parade ground within two hours later the explosion. Galloway and Individual George Fielding were sent to the hospital in Charleston, where Galloway died a few days later; Fielding was released after six weeks.[59] [60] The other wounded men and the remaining Spousal relationship troops were placed aboard a Amalgamated steamer, the Isabel, where they spent the dark and were transported the side by side forenoon to Pull a fast one on's relief ship Baltic, resting outside the harbor bar.[61]

Major Robert Anderson'southward telegram, April 18, 1861

Steamship Baltic, oft Sandy Claw

Thursday, April eighteenHon. Due south. Cameron, Sec'y. of War, Washington, D. C.

Sir—Having defended Fort Sumter for thirty-4 hours, until the quarters were entirely burned, the main gates destroyed by fire, the gorge wall seriously injured, the magazine surrounded by flames, and its door closed from the effects of the oestrus, four barrels and three cartridges of powder only being bachelor, and no provision but pork remaining, I accepted terms of evacuation, offered past Gen. Beauregard, beingness the same offered past him on the 11th inst., prior to the kickoff of hostilities, and marched out of the fort Sunday afternoon, the 14th inst., with colors flight and drums beating, bringing away company and individual property, and saluting my flag with l guns.ROBERT ANDERSON

Major First Arms.[62]

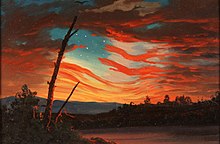

Anderson carried the Fort Sumter Flag with him due north, where it became a widely known symbol of the battle and rallying point for supporters of the Spousal relationship.[63] This inspired Frederic Edwin Church to paint Our Banner in the Sky, described as a "symbolic landscape embodying the stars and stripes." A chromolithograph was and then created and sold to benefit the families of Union soldiers.[64]

-

[Top] A photographic view of the Hot shot Furnace at right shoulder angle and a 10-in. columbard cannon pointing to Charleston;[65][Lesser] Exterior view of Gorge and Sally Port Ft Sumter April 1861 subsequently its surrender

-

Views of Ft Sumter; [Bottom] View of right angle

-

Right angle gorge of Ft Sumter—Sally port at correct

-

View of the Gorge and Emerge Port

-

View of western part of Gorge

-

[Top] View of gorge and Sally port; [Bottom] Left gorge Angle

-

View of Left gorge angle Sally Port would be at far left

-

View of Left flank

-

Panormanic View of Left shoulder Bending at left with a 2nd Hot Shot furnace and Left confront at right; Ft Sumter 1861; flight the Confederate Flag

-

At Left N west castmates [left angle]; at correct can exist seen the offset of the right angle

Backwash

Confederate Flag flight in Fort Sumter after the 1861 surrender

The battery of Fort Sumter was the first military activeness of the American Civil War. Following the surrender, Northerners rallied backside Lincoln'due south call for all states to ship troops to recapture the forts and preserve the Union. With the scale of the rebellion apparently pocket-size so far, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers for ninety days.[66] Some Northern states filled their quotas quickly. There were so many volunteers in Ohio that inside xvi days they could have met the full call for 75,000 men by themselves.[67] Other governors from border states were undiplomatic in their responses. For example, Gov. Claiborne Jackson wrote, "Not ane man will the land of Missouri furnish to bear on whatsoever such unholy crusade", and Gov. Beriah Magoffin wrote, "Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states."[68] The governors of other states yet in the Matrimony were equally unsupportive. The telephone call for 75,000 troops triggered 4 additional slave states to declare their secession from the Union and join the Confederacy.[69] The ensuing war lasted iv years, effectively ending in Apr 1865 with the give up of Full general Robert East. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia at Appomatox Courthouse.[70]

Charleston Harbor was completely in Amalgamated easily for near the entire 4-year elapsing of the state of war, leaving a pigsty in the Union naval blockade. Marriage forces conducted major operations in 1862 and 1863 to capture Charleston, first overland on James Island (the Battle of Secessionville, June 1862), and so by naval set on against Fort Sumter (the First Boxing of Charleston Harbor, April 1863), then by seizing the Confederate arms positions on Morris Island (beginning with the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, July 1863, and followed by a siege until September). After pounding Sumter to rubble with artillery fire, a last amphibious functioning attempted to occupy it (the Second Boxing of Fort Sumter, September 1863), merely was repulsed and no further attempts were made. The Confederates evacuated Fort Sumter and Charleston in February 1865 as Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman outflanked the urban center in the Carolinas Entrada. On April 14, 1865, iv years to the twenty-four hours later lowering the Fort Sumter Flag in surrender, Robert Anderson (by then a major full general, although ill and in retired status) returned to the ruined fort to raise the flag he had lowered in 1861.[71]

Two of the cannons used at Fort Sumter were later presented to Louisiana State University past General William Tecumseh Sherman, who was president of the university before the war began.[72]

Tributes

Civil War Centennial Issue of 1961

The U.Due south. Post Part Department released the Fort Sumter Centennial upshot every bit the beginning in the series of five stamps marker the Civil War Centennial on Apr 12, 1961, at the Charleston post office.[73] The stamp was designed by Charles R. Chickering. It illustrates a seacoast gun from Fort Sumter aimed by an officer in a typical uniform of the time. The groundwork features palmetto leaves akin to bursting shells. The state tree of Southward Carolina, the palmettos suggest the geopolitical expanse opening Ceremonious War hostilities.[74] This stamp was produced by an engraving and printed past the rotary process in panes of fifty stamps each. The Postal Department authorized an initial printing of 120 million stamps.[74]

See as well

- Raising the Flag at Fort Sumter

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ Dyer, Volume III, p. 831

- ^ a b c d e Welcher, p. 699.

- ^ Kennedy, p. one.

- ^ "Fort Sumter Battle Summary". National Park Service. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "FORT SUMPTER FALLEN". nytimes.com. April 15, 1861.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 235–235.

- ^ Davis, pp. 25, 127–129.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 67–69.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 246–248.

- ^ Burton, pp. 4–five.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b Davis, p. 120.

- ^ Burton, pp. 6, 8.

- ^ Detzer, pp. i–2, 82–83.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 110–120.

- ^ Davis, pp. 121–122.

- ^ a b Detzer, p. 78.

- ^ Burton, p. 7.

- ^ "Fort Sumter National Monument". National Park Service. Archived from the original on May four, 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 131–136.

- ^ Eicher, p. 35.

- ^ Burton, pp. 12–16.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 264–266.

- ^ Burton, pp. 17–20.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 155–161.

- ^ Buchanan, p. 178.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Burton, pp. 29–30.

- ^ "Fort Sumter National Monument". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2011.

- ^ Eicher & Eicher, p. 810.

- ^ Eicher, p. 36.

- ^ Davis, pp. 136–137.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 261–263.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 212–214.

- ^ Detzer, p. 212.

- ^ McPherson, pp. 268–271.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 225–231, 249.

- ^ Burton, pp. 33–35.

- ^ McPherson, p. 272.

- ^ Davis, pp. 133–136.

- ^ Ward, Burns & Burns 1990, p. 38.

- ^ Davis, pp. 139–141.

- ^ Burton, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 256–267.

- ^ Eicher, p. 37.

- ^ Daily Globe October 20, 1884 p. 4

- ^ The Princeton Union 9 September 1897 p. 8

- ^ a b Davis, p. 146.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 268–271.

- ^ Davis, pp. 147–153.

- ^ Burton, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Davis, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Davis, pp. 152–157.

- ^ Burton, pp. 49–51.

- ^ a b Detzer, pp. 292–300.

- ^ Burton, pp. 51–55.

- ^ Davis, pp. 157–160.

- ^ Burton, pp. 53–55.

- ^ Eicher, p. 41.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 308–309.

- ^ Ripley, p. 20.

- ^ "Major Anderson's dispatch to the War Department". The New York Times. Apr 19, 1861. p. one – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Detzer, pp. 311–313.

- ^ "Our Banner in the Sky". Olana State Celebrated Site. Retrieved Jan 12, 2013.

- ^ See Ft Sumter Map "Battles and Leaders of the Civil State of war Vol 1 p.54

- ^ McPherson, p. 274.

- ^ "Fight for the Colors, the Ohio Battle Flags Collection, Civil War Room". Ohio Historical Society. Archived from the original on Dec 11, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Widmer, Todd (Apr 14, 2011). "Lincoln Declares War". opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com. Opinionator. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 52–53, 72–73.

- ^ Eicher, pp. 820, 841.

- ^ Eicher, p. 834.

- ^ "Louisiana Land University Regular army ROTC Unit of measurement History". Louisiana State University. Retrieved Jan 24, 2015.

- ^ "Civil War Centennial Issue". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Ceremonious State of war Centennial Upshot", Arago: people, postage stamp & the postal service, National Postal Museum online, viewed March sixteen, 2014.

Notes

- ^ The weapons in the arsenal consisted of almost xviii,000 muskets, 3,400 rifles, over 1,000 pistols, and a few arms pieces including five 24-pound field howitzers.[xx] [21] [22]

- ^ Detzer comments that Ruffin claimed he fired the showtime shot,[49] when Ruffin did not actually practice so.[48]

References

- Buchanan, James (1911). The Works of James Buchanan: Comprising His Speeches, State Papers, and Individual Correspondence. ISBN9781623767440.

- Burton, Eastward. Milby (1970). The Siege of Charleston 1861–1865 . Columbia, SC: University of Southward Carolina Press. ISBN978-0-87249-345-2.

- Cooper, William J. (September 11, 2012). We Have the War Upon United states: The Onset of the Civil War, November 1860 – April 1861. New York City, NY: Vintage. ISBN978-0-307-96088-7.

- Davis, William C. (1983). Brother confronting Brother: The War Begins . Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN978-0-8094-4700-8.

- Detzer, David (2001). Allegiance: Fort Sumter, Charleston, and the Beginning of the Ceremonious War . New York City, NY: Harcourt. ISBN978-0-xv-100641-0.

- Eicher, David J. (2001). The Longest Nighttime: A Military History of the Ceremonious State of war . New York City, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN978-0-684-84944-vii.

- Eicher, John H.; Eicher, David J (2001). Civil War Loftier Commands. Stanford, CA, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN978-0-8047-3641-one.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil State of war Battleground Guide (ii ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN978-0-395-74012-5.

- McPherson, James K. (1988). Battle Cry of Liberty: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York City, NY: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-503863-7.

- Ripley, Warren (1992). Wilcox, Arthur M. (ed.). War'south First Death Accidental. The Civil War at Charleston (16th ed.). Charleston, SC: Evening-Postal service Publishing Co. OCLC 636046368.

- Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken; Burns, Ric (1990). The Ceremonious War, an Illustrated History. New York City, NY: Knopf. ISBN978-0-394-56285-eight.

- Welcher, Frank J. (1989). The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington, ID: Indiana University Press. ISBN978-0-253-36453-ane.

Further reading (from earliest to most recent)

- Primary sources

- Anderson, Robert; Pickens, F.Westward. (January 1861). Correspondence and other papers relating to Fort Sumter. Charleston, South Carolina.

- Anderson, Robert (Apr nineteen, 1861). "The Defence of Sumter. Detailed Account of the Defence of the Fort, by Major Anderson". The New York Times. p. 1 – via newspapers.com.

- The Battle of Fort Sumter and Start Victory of the Southern Troops. April 13, 1861. Total accounts of the Bombardment, with Sketches of the Scenes, Incidents, etc. Compiled importantly from the detailed reports of the Charleston Press. Charleston, South Carolina. 1861.

- Harris, W. A. (1862). The record of Fort Sumter, from its occupation past Major Anderson, to its reduction by Due south Carolina troops during the assistants of Governor Pickens. Columbia, South Carolina: Columbia, S.C., S Carolinian Steam Job Printing Office.

- Doubleday, Abner (1876). Reminiscences of Forts Sumter and Moultrie in 1860–61. New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 1320168.

- Chesnut, Mary (1905). Diary of Mary Chesnut. Fairfax, Virginia: D. Appleton and Visitor. OCLC 287696932.

- Secondary sources

- Hendrickson, Robert (1996). Sumter: The Starting time Day of the Civil War. New York: Promontory Press. ISBN978-0-88394-095-2.

- Klein, Maury (1997). Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN978-0-679-44747-4.

- Hatcher, Richard Westward. (Winter 2010). "The Problem in Charleston Harbor: Fort Sumter and the Opening Shots of the Civil State of war". Hallowed Ground. Archived from the original on January 1, 2015.

External links

- National Park Service battle description

- Fort Sumter National Monument

- Battle of Fort Sumter: Maps, histories, photos, and preservation news (CWPT)

- Crisis at Fort Sumter

- Details of requests for give up prior to the battle

- Discussion of transfer of federal holding within state boundaries

- Newspaper coverage of the Battle of Fort Sumter

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Fort_Sumter

0 Response to "what fort was attacked to begin the civil war"

Post a Comment